|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

It was meant to be just a college job. Amy Hunn was in Denver, majoring in interior design at the Art Institute of Colorado in the early aughts, and working part-time at a small barbershop whose owners had done well enough to extend to three locations, with a fourth on the way. Hunn booked appointments, answered phones, and did laundry along with any other odd task that might pop up. Having grown up with parents who owned a hardware store, “doing it all” wasn’t anything new for the undergrad, but it seemed like a side gig she’d eventually leave once she had graduated. That was 18 years ago.

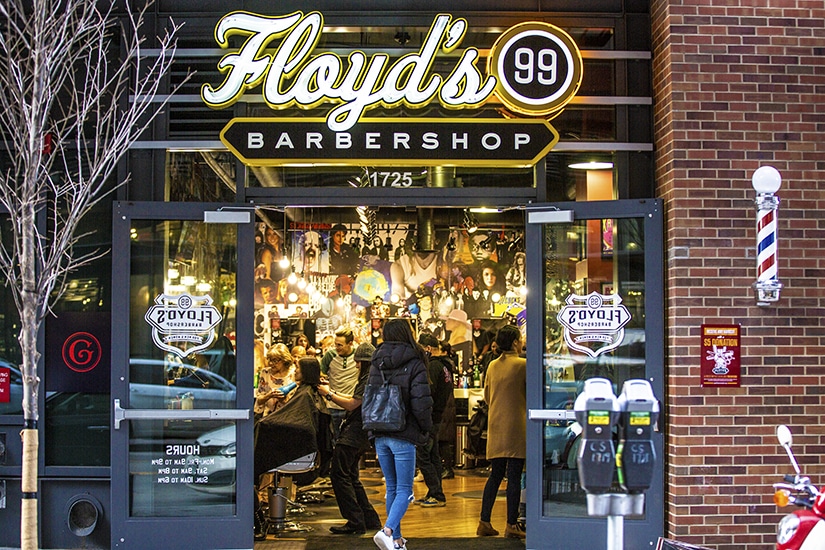

The small but prosperous barbershop business was Floyd’s 99 Barbershop, whose locations have multiplied from three to over 120 in 14 states. The Floyd’s brand has found a way to still embody the community atmosphere of the local barbershop, but in an authentic, repeatable, and efficient manner. Those efficiencies are a credit to Hunn—now the company’s vice president of construction and facilities—who back in 2002, was getting ready to see what else the world had to offer.

“I was looking for restaurants, hotels, any kind of commercial stuff in my field,” Hunn remembers. Despite the search, long hours spent in front of a computer running CAD drawings didn’t seem like the future she wanted. “I finally got an interview and at the same time, the owners of Floyd’s reached out and wanted to talk with me about this growth they were going to be going through. They wanted to know if I wanted to be part of it and if I would stay. I figured I’d give it a shot.”

It’s easy to imagine the interior of a Floyd’s barbershop when Hunn talks about her early days with the company. In a way, Hunn’s memories are a perfect reflection of the interiors she’s helped create. Huge collage poster walls adorned with bands from yesteryear to the current times are complemented with simple, sleek leather barber chairs. It’s chaos with class. “The company was really just starting to build its infrastructure outside of the three owners running the day-to-day,” Hunn says. “They were looking to put systems and processes in place to be able to franchise and scale the brand.” The VP says titles were an afterthought because it seemed like everybody was often doing everything.

There was no job too big or too small, and that includes taking out a garbage or emptying a hair trap. But Hunn also ran the company’s POS software including a company-wide transition to a new vendor in 2014. “I think sometimes people get caught up in the titles and they like to think that something isn’t their job,” Hunn says. “But here, everyone thinks they’re responsible for something bigger, not just whatever their title might say. I think it’s such a great philosophy and way of approaching your work.”

The philosophy is obviously successful, as even amidst a pandemic, Floyd’s continues planning for further expansion. Since Hunn has grown up with Floyd’s, she says each new store feels like one of her children being sent out into the world.

But with that expansion, Hunn has had to grow her own depth of focus. “As we’ve increased in size, we’ve had to really hone our processes and streamline things to become more structured,” she explains. “We’re focused on continuing to support our growth both corporately and with our franchise partners, and we have to be able to show and prove that our processes work.”

Hunn says continuing to build lasting relationships with trusted vendors across the country has helped take projects that were once daily panic attacks into now weekly check-ins. “It’s been so helpful to find contractors and architects who you can hand parts of the project off to,” she says. “They’ve proven themselves with us already, and there’s a level of trust there that makes things so much easier.”

Relationships are a key component of Floyd’s business model with vendors, customers, and the communities in which it operates. “We want to be part of our communities, which is why I think we’re so focused in giving back in all the ways that make me proud to be part of the company,” Hunn says. In several of Floyd’s California locations, the company has commissioned huge murals commemorating movies or artists from the area like The Karate Kid in Encino, Gwen Stefani in Tustin, and Sublime in Long Beach.

Hunn has been with Floyd’s long enough that her own DNA might as well be part of each and every new shop, though she tries to downplay the assertion, focusing instead on what she loves about the interiors of the Floyd’s brand. “Obviously I love our poster walls,” Hunn says. “I love the idea that while you’re sitting and getting your hair cut, people can sort of search through the rubble and find their favorite band or artist. But the things that I really think are the coolest are probably the things people don’t even notice, like how we were able to take an awkward column and really integrate it into a design. Those little victories always make me proud.”

More than any interior, Hunn says, are the pictures she sees online of young men and women celebrating their high school graduations; the kids she remembers getting their first haircuts at Floyd’s remind her of just how far she’s come. And with the company’s growth over her 18 years, wherever those young people wind up, there will likely be a Floyd’s 99 Barbershop nearby.