|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

On June 24, 2021, University President Peter Salovey and Provost Scott Strobel sent an important message to members of the Yale community regarding their commitments to mitigating climate change. In that message, they detailed a multitiered approach that would allow the university to reach a carbon-zero status by 2050 by rethinking energy consumption and other related factors.

“The world’s research universities need to accelerate progress on what they are uniquely positioned to do, and Yale must lead these efforts,” the duo wrote. “Every part of the university must offer solutions and commit to environmental sustainability.”

Keith Fordsman is doing his part to respond to the 2050 mandate. As Yale’s capital programs director, he leads a team responsible for long-term financial and space planning. Each year, the school receives and allocates donor funds, endowments, and departmental contributions to power about $450 million in campus renovations, acquisitions, and new construction projects. Yale’s new carbon reduction targets are changing the way Fordsman’s team operates and will impact the next decade of capital planning.

“Changing state codes and stakeholder expectations requires wholesale changes in how buildings are created and operated,” he says. “The small and large changes we make add up to have a real impact.” Fordsman manages a team of 34 people who work on 400 buildings across 20 million square feet. Each year, they complete about 300 projects on the university system’s three campuses.

Fordsman’s vendors applaud the capital programs director for his ability to enable the team to execute such a feat. “Keith has been—and continues to be—an honest, trusted partner and friend to myself and Turner,” says a colleague at Turner Construction Company, adding that Fordsman is adamant about industry advancements and promoting sustainability, something demonstrated clearly in Yale’s project approach. “His expertise serves as a testament to his ability to consistently deliver projects of exceptional quality and lead high-functioning teams while [motivating] both designers and construction managers to do something extraordinary on all projects.”

Nearly two decades in the hospitality sector prepared Fordsman to thrive in higher education. He started in construction management and worked for a private developer before transitioning to roles with hotel companies. In 2005, Fordsman joined Starwood Hotels & Resorts Worldwide Inc. and spent more than 11 years developing its flagship properties in places like the W Times Square; the St. Regis Bal Harbour Resort in Miami Beach, Florida; Mexico City; Aspen, Colorado; and a new Westin Vacation Ownership in Maui, Hawaii.

“Changing state codes and stakeholder expectations requires wholesale changes in how buildings are created and operated. The small and large changes we make add up to have a real impact.”

Keith Fordsman

Dealing with resort plans and hotel customers in different regions helped ready him for the competing demands of academia. “Hospitality prepared me well to lead in higher education because of the diversified experience in brands, regions, and products combined with the experience I gained in understanding how different users engage with the physical space,” he says.

At Starwood, Fordsman thought about how guests arrive at the resort, unload their car, and check into their room. At Yale, he considers how graduate students enter a lab space at 2:00 a.m. to check on a critical experiment that goes around the clock. “I’m an interpreter between the user group, the design team, and everyone else involved,” Fordsman says, adding that he often commissions 3-D virtual models so users can visualize labs and other complex spaces as part of the approval process.

These factors—intended use and the university’s carbon reduction goals—guide every project Fordsman’s team completes. “No new project can have an adverse effect on our carbon footprint,” he says. “For every new building I create, I have to reduce the consumption of a legacy asset.” That’s especially challenging at a campus founded in 1701. Yale’s oldest building, Connecticut Hall, commenced construction in 1750. Revolutionary War soldier Nathan Hale slept there while attending Yale in 1773.

An energy management plan is helping Yale’s leaders achieve their carbon reduction goals. A central power plant produces thermal energy for most buildings and delivers steam and chilled water via underground tunnels. Fordsman and his colleagues optimized delivery in 2020 to improve chilled water production. They are also leveraging a clean utility grid to avoid fossil fuel consumption for heat and electricity while investigating ways to disconnect existing buildings from steam.

“No new project can have an adverse effect on our carbon footprint. For every new building I create, I have to reduce the consumption of a legacy asset.”

Keith Fordsman

In late 2022, the capital programs team will break ground for Yale Divinity School’s Living Village residential complex. The housing facility—slated to open in 2024—will fulfill the sustainability requirements of the Living Building Challenge. The Living Village, which will be home to about 150 students, replaces nearby student apartments that date back to 1957.

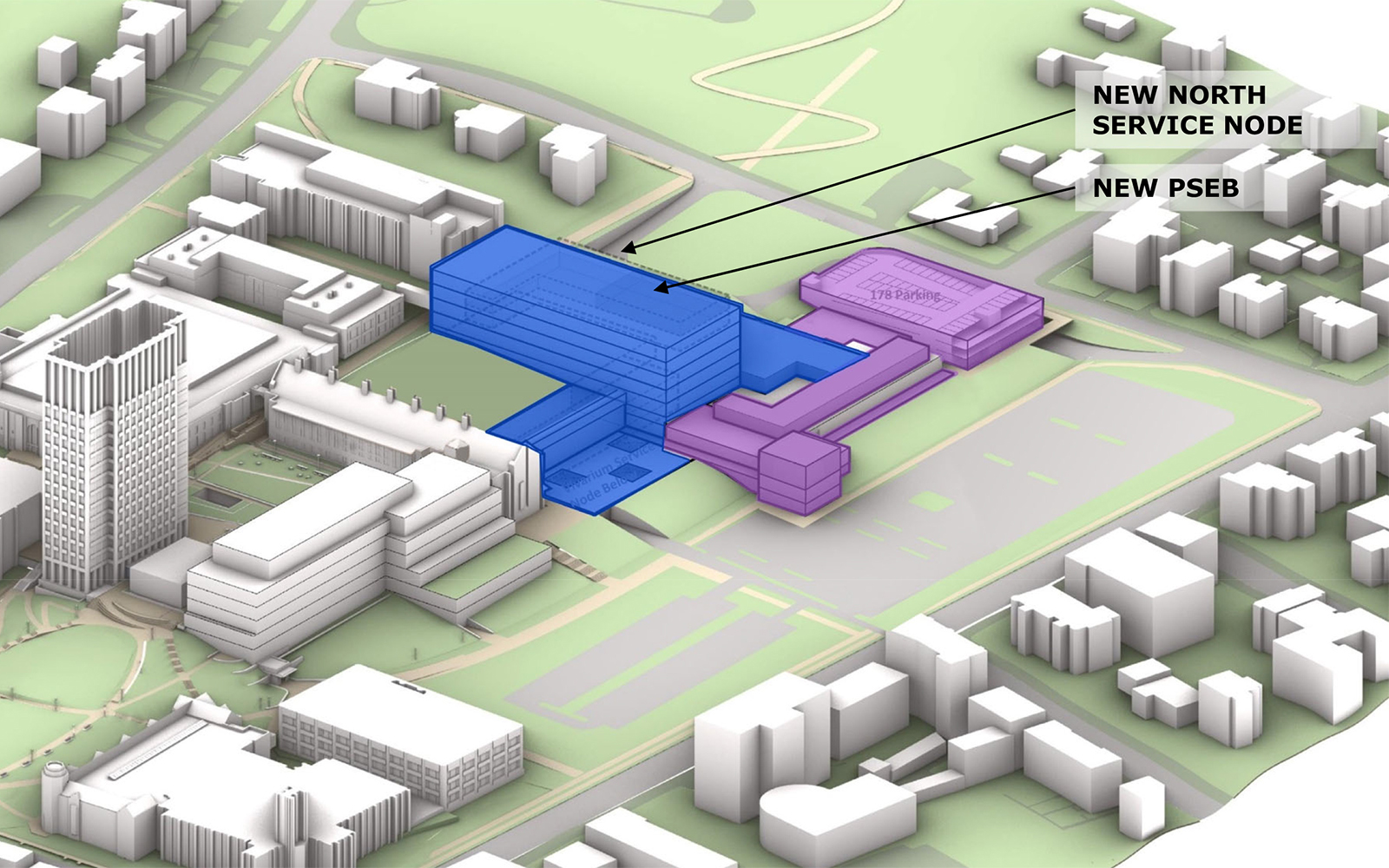

Currently, Fordsman and others are working together on a new physical science and engineering building, a 400,000-square-foot multidisciplinary facility that Fordsman expects to start work on in 2023. It will open within five years and will accommodate new faculty and research labs while serving as a hub for Yale’s quantum science, engineering, and materials initiatives and an expansion of its Instrument Creation Center.

After more than five years in New Haven, Fordsman is settling into higher education and shedding the for-profit thinking that propelled him in the world of hotels and hospitality where he once developed and sold resorts in billion-dollar deals. Instead, he’s at Yale, where his team creates buildings that cost $1,000 per square foot—buildings designed to be present for centuries.

Still, Fordsman sees great value in the important work he’s doing. “People who come here want to cure cancer, enter politics, and lead business innovations . . . and we are involved in creating the spaces where they do those things,” he says. “How do you measure the value of these projects compared to those who will come to Yale and then go on to change the world?”