|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

The Smithsonian Institution is renowned as the world’s largest museum and research complex, offering vivid interaction through educational exhibits that span 19 individual museums and one gigantic zoo. Since 1846, it’s upheld one important mission: to be “an establishment for the increase and diffusion of knowledge.”

Judson McIntire, the Smithsonian’s associate director for program management, finds personal significance in this founding principle. “We need to keep that in mind,” he says. “Everything we do is for the benefit of scholarship and education and the passing on of new and historic knowledge.” In his role, that means employing his extensive background in architecture and engineering to flourish in the institution’s program and project management arena, overseeing the necessary repairs and modifications, managing the capital plans for revitalization and new construction, and having a hand in the latest developments.

It’s an incredible undertaking, especially for an organization that is so devoted to being a public resource that, until the coronavirus pandemic, would remain open 364 days per year, coordinating its upkeep around the millions of visitors curiously wandering the facilities. Even amid the nationwide shutdown, the Smithsonian was careful to maintain engagement through virtual events and exhibits, and has remained on track with a gradual, safe reopening plan.

“The end result is to improve the performance and care of our collections and the comfort of our visitors,” says McIntire, who has been with the Smithsonian for more than 25 years. Every single exhibit is a large collaboration between design, architectural, and staff stakeholders who coordinate the programs and intellectual scenes. Often times, this results in a marriage between building and showcase, or as McIntire puts it, “in the best cases, the shell and the exhibit can complement each other, so you end up with the very best solution.”

A prime example of this is the African American History and Culture Museum, which reopened to the public in September 2020. “The architecture and exhibit design were thoroughly integrated in the form of the [exterior] building and the formation of the interior,” McIntire explains. The building facades include numerous openings, or lenses. “Lenses are windows from the exhibit galleries onto the landscape that provide context.”

For instance, a museum visitor might walk the hall and discover a lens that focuses on the outside Washington Monument, helping them interpret the stories inside the exhibit, leading them to “sample the Washington Monument lens in the military hall,” McIntire suggests. He notes that these lenses also allow natural light to filter in, giving the eyes a break.

Even the form of the building itself is intentional, he continues. “It’s inspired by West African heritage, and the headdress of a structural human sculpture that was really the inspiration for the tiered inverted pyramid form of the building. That profile was inspired from this West African sculpture and then to the materiality of the façade, which is 3,600 cast aluminum [bronze colored] panels that use a theme, sort of an abstracted form of cast iron work that might have been crafted by enslaved Africans in New Orleans and Charleston. So, again, it’s tying the theme, the history, and the artistry of the African American culture to the design of the building.”

The museum, which McIntire had the opportunity to manage oversight for its planning, design, construction, scheduling, budget, and opening, is in an extremely precious location, being seated beside the Washington Monument. “Everything from the site plan and the open space, the views, the cornice height, the materiality, and the landscape was subject to discussion, review, and approval both by the external agencies as well as the National Historic Preservation Act Section 106 process,” says McIntire, adding that it was also addressed through 35 public consultations. “It was touched by so many minds and so many parallel processes. In addition to the design there are over five thousand contributors to the project.”

November 2015 was the target opening date, in tandem with the anniversary of the 13th Amendment that abolished slavery in the US. Unfortunately, McIntire explains, constructing a 400,000 square foot museum in a short period of time after decades of efforts to establish funding and clearance took a bit longer due to unforeseen conditions. “The founding director, Lonnie Bunch, had an enormous task to raise two hundred and seventy million dollars and then some to reach half of the $540 million total project costs,” he describes.

It opened 10 months later as the final product of Bunch’s vision. “He intended for the museum to be a place where conversation about race would happen,” McIntire explains, “so I think he planted the seed and created that environment for discussion and education about race.”

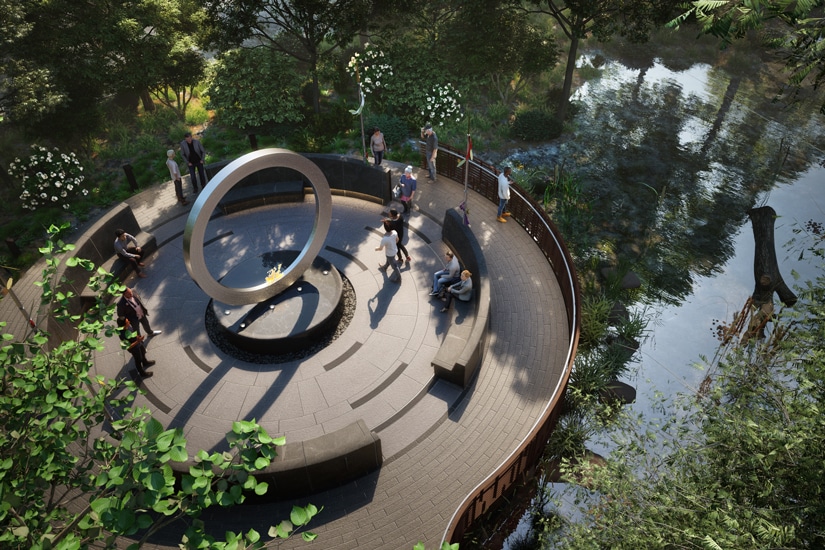

In addition to his work with the National Museum of African American History and Culture, McIntire was also involved in the Smithsonian’s new National Native American Veterans Memorial on the grounds of the National Museum of the American Indian. At the time of speaking, the project is set to debut on Veteran’s Day 2020. McIntire collaborated with Quinn Evans, the architect of record for the project, as well as Native American artist Harvey Pratt and BAU Architects, designers of the Memorial. “Harvey is a unique individual,” McIntire muses. “He’s such a fine man, and I’ve been so privileged to work with him.”

Pratt was principal of the design team that won the competition, and McIntire describes the artistic concept for the memorial as being a “very lovely and appropriately simple design.” It incorporates symbols and elements of fire, water, drums, cardinal points, and a circle shape—all seen in many native traditions. “He’s supervising the fabrication of the warrior ring, the stainless steel circle that is the focus of the of the memorial,” McIntire says. “Other parts of the design that Harvey created are the lances and feathers. He always says that tribal paths are the same; they lead to the same place, but they might go in different directions. They have a common ending.”

Aside from being a place for the public to admire Pratt’s design and honor the military service of Native American veterans, McIntire explains that the Memorial will serve as a meaningful location for various Native tribes. “This will be a place where tribal people can come and contemplate and meditate and hold those rituals, hold ceremonies,” he describes. “It’s a special place for the native people, and we will be open to them for these ceremonial opportunities that are just incredible.”

The National Museum of African American History and Culture and the National Native American Veterans Memorial came across McIntire’s desk in different ways. The program management director asked to be part of the former—and actually had to be selected to contribute—while the latter was an opportunity that serendipitously appeared in his portfolio of facilities. Both projects were awarded to him based on his decades of experience, skills, and workstyle, something his partners at engineering firm AECOM can attest to.

“Jud has a great easygoing manner and the ability to let a conversation unfold, such as when a design idea is being explored, and when to step in, wrap up the discussion, and reach a conclusion,” says Alan Harwood, vice president and director of urban planning at AECOM.

Nonetheless, McIntire remains humble and appreciative. “I think it’s such a privilege and a great honor for me to work at the Smithsonian, but also to have been part of both of these, these special and important projects,” he says. “We all learn through life, but I think having close relationships with both the African American Museum and the American Indian Museum, it’s so personally enriching and broadening to have had that and to have learned so much from it.”