|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

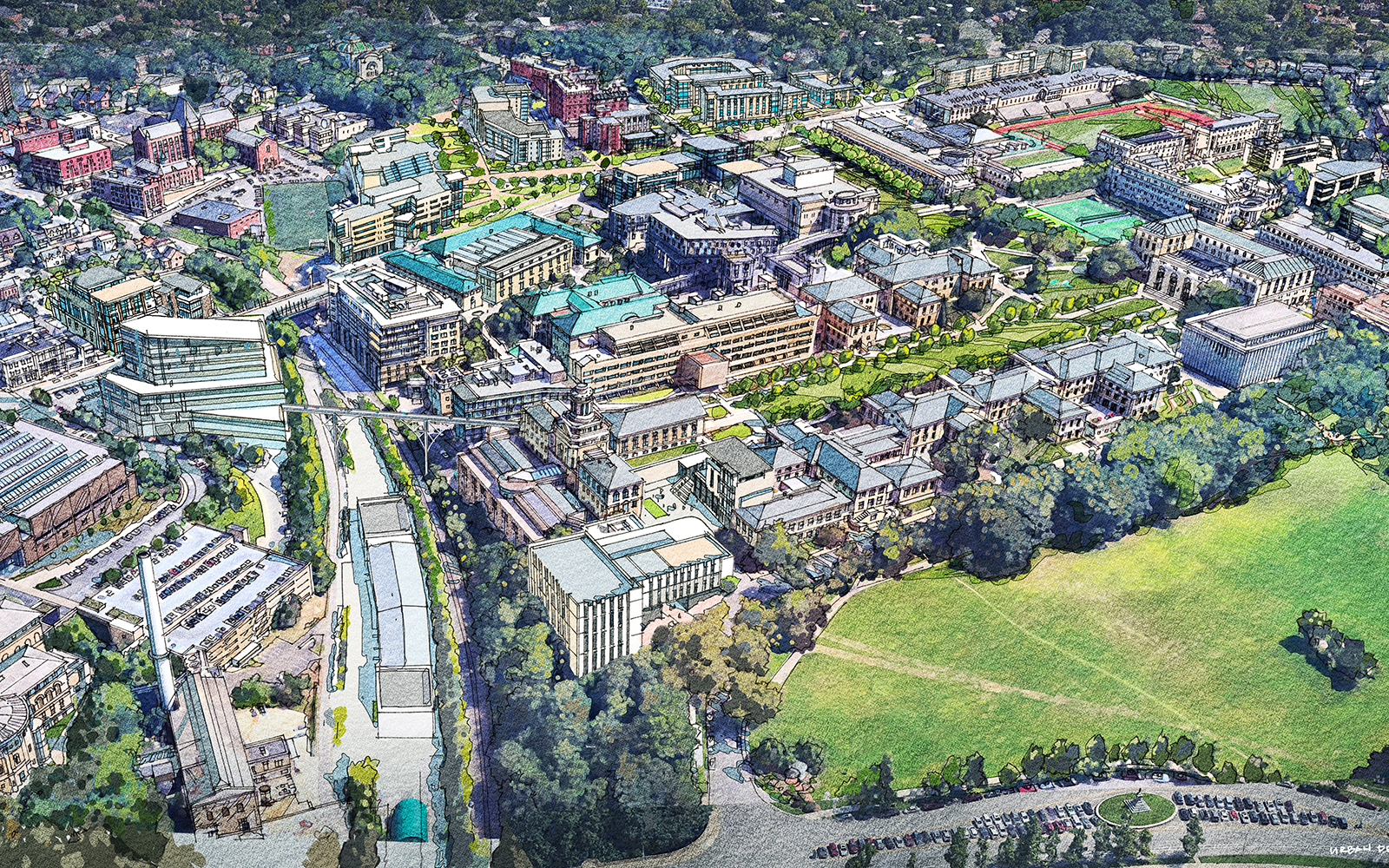

Carnegie Mellon University’s campus in Pittsburgh is immersed in an ambitious master plan that lays out the university’s development activity for the next 10 years. And Bob Reppe, senior director of planning and design, leads the charge to make it happen.

“We see the plan as both a physical plan as well an aspirational document,” Reppe says. “It includes definite projects, as well as a sort of wish list of topics. Most institutional master plans don’t do that. In addition to development sites, it also folds in the development of campus open spaces, mobility policies, neighborhood engagement, and similar considerations.”

The planning process was time-intensive, but ultimately makes implementation easier, he explains. “We developed it in conjunction with the city of Pittsburgh, which takes a kind of carrot-and-stick approach. The ‘stick’ is the long planning and review process, but the ‘carrot’ is that any of the projects included in the approved plan will be developable as soon as we’re ready to move forward on them. In comparison, a standalone building proposal could be subject to a much longer review that could include city council,” he says.

Reppe’s roots in the field extend to his childhood sandbox, where he and his brother started out building the usual castles, and eventually moved to more complex structures, such as dams and little towns. The boys were also big fans of LEGO bricks, part of their annual Christmas loot for several years.

His interest was further piqued in high school by the description of “urban and regional planning” in some college informational materials, and he later earned a BA in that field from the University of Minnesota at Duluth.

Reppe adds that the school’s language requirement also sparked an interest in international relations. “I chose to learn Russian and was actually able to spend several months living and studying in that country. I later wrote a report on the impact of Soviet architecture and planning in the region.”

As an undergrad, Reppe interned with the Arrowhead Regional Development Commission in Duluth. “It was policy heavy,” he says, “concentrating on transportation and funding. I realized that I liked working for the common good but sought a more concrete way to improve the public realm.”

He later enrolled at the University of Texas, which offered an appealing architecture program. The department had plenty of designers, but few planners; Reppe knew much about planning, but little about design. After what he calls a “crash course in architecture,” he’d caught up to his classmates.

His academic advisor was also a practicing architect, and Reppe gained valuable experience in developing master plans for developers and builders. “It was a great experience for me because it went beyond simply creating drawings. I assembled complete packages that demonstrated not just what was planned, but why it was being planned that way. And I learned to use drawings as communication tools,” he says.

Reppe moved to Pittsburgh to join the Pittsburgh Department of City Planning as an urban designer, and then ultimately the zoning administrator. He worked for the city for nine years before joining the university.

“One of the Carnegie Mellon master plan’s principles holds that building designs should reflect and reinforce the university’s values and be timeless,” he says. “And the areas between them are important, too. Essentially, we want to use our space in the best ways we can.”

Reppe points out that the campus functions essentially as a small city, so urban development principles are applicable. “When you’re on campus, you’ll see a wonderful mix of people,” he says. “Everyone from senior citizens to undergrads, faculty and international students, teenagers from local high schools. Even lots of little kids—we have two day-care centers on campus.

“We are also home to the Osher Lifelong Learning Institute, which offers courses taught by members, volunteers, faculty from CMU and other regional colleges and universities, and representatives from community organizations,” he says.

One aspect of the plan is directed toward better relationships with the city. “For decades, the university had been inward-looking,” Reppe says. “Until recently, none of our buildings had a main entrance that faced Forbes Avenue, which is Pittsburgh’s key artery. We need to embrace our involvement in western Pennsylvania’s economic engine.”

That’s reflected in a planned 300,000-square-foot science facility that will combine engineering labs, academic facilities, and gallery space, and the repurposing of an abandoned steel mill for an expanded robotics facility. “Robots need room to run, so we’ll develop buildings to accommodate those needs,” he says.

Student housing falls under the umbrella of the master plan, and the university recently opened an on-campus 270-bed suite building and a 175-apartment building; more are in the offing. “We want to ensure that every undergrad who wants campus housing can have it. And it won’t be in old-style dorms, either,” he says.

He adds that the new residences will help ease Pittsburgh’s own housing pressures. “We are committed to working with adjoining neighborhoods,” Reppe says, “so we regularly attend community meetings to offer support and input.”

Sustainability is a constant concern. “We built the country’s first LEED-certified dorm in 2005,” Reppe says. “Ninety percent of our construction over the past 10 years has been LEED certified as well. We use renewable electricity on campus, and extensive water-management practices, such as collecting and filtering storm water, then reusing it in cooling towers.” Establishing trust-based relationships is essential to the plan’s success.

“These projects involve many, many people,” Reppe says, including architects, builders, vendors, campus administration, neighbors, and others. “Part of my job is to enable all of these experts to work together. They know that Carnegie Mellon is a fussy client—but also that we’re dedicated to doing great things. It’s why we always strive for cooperative solutions rather than making demands.”